Today, there was a major 7.0 earthquake that affected Northern California. This quake also prompted warnings for potential tsunami. And, once again, I am seeing and getting the question, did anything go over the Emergency Alert System (EAS) about the quake?

As someone who has been through my share of earthquakes, I can definitely tell you how they can just come up out of nowhere and just happen. Unlike a tornado or a hurricane, there is normally not much time to prepare for the impacts of an earthquake.

The main reason why EAS in its current form is not effective for earthquakes is because of latency, the amount of time it takes from when an alert is received to the time when it is actually broadcast.

How EAS gets from here to there…

EAS is received through two different methods, the legacy method which is receiving another radio station that is carrying the alert or through the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System (IPAWS).

When an alert comes through the legacy method, it has to be first broadcast by the station that is originating the alert, this station could be the National Weather Service (NWS) on their 162 MHz weather broadcast stations. The next station downstream then records the message and then relays it by alerting its programming. That alert is then recorded by other stations downstream which will then interrupt their broadcast to play the message. Depending on the length of the message, it can take several minutes before an alert is received by a “Participating National” (PN) broadcast station on the low end of the food chain.

When an alert comes through IPAWS, it is sent to all EAS receivers that indicated that they want to receive alerts from a particular county. Once the alert is received, the EAS could immediately interrupt the broadcast and play the recorded message that comes on a MP3 file or read to the listener using text to speech in the EAS unit.

Bad policy from L Street does not help

Because of a recent FCC rule change, messages received through the legacy method will take longer because of a very bad mandate the agency put in called “CAP Polling”. With CAP Polling, the EAS box must delay the interruption of the broadcast for up to 10 seconds just in case the same message is received through IPAWS. The idea here is that the preference is to use the IPAWS message. This is because the IPAWS message, which uses the Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) is more robust and can contain text, graphics, photos and sound. The intention of CAP Polling is so those who are hard of hearing would be able to see more robust information on the crawl of the TV screen. CAP Polling provides no benefit to radio, but radio stations were required to upgrade their EAS firmware and in some cases, had to spend 4-figures to purchase a new EAS unit.

The problem with CAP Polling is that one of the biggest alert originators in the country does not use IPAWS for EAS. That originator is no other than the good ol’ National Weather Service. If anything, NWS stopped sending weather alerts through the non-EAS channel in IPAWS. Certain types of alerts do get forwarded to Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) but not to broadcast EAS via IPAWS.

Therefore, if an earthquake takes place, by the time that many would get the alert, the shockwaves would have already passed. Of course, anyone who has experienced earthquakes in the past know that when you feel one bigger one, expect aftershocks.

Look to Japan to get this right

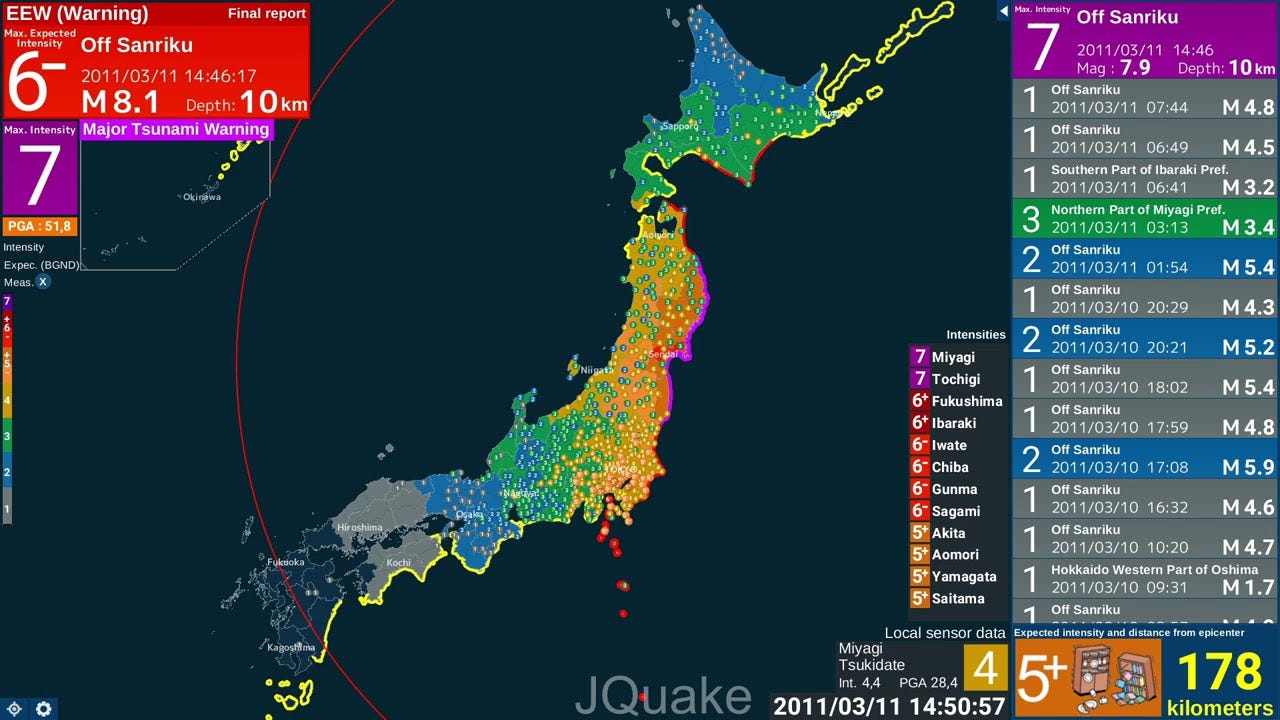

Technology does exist to accommodate more instantaneous alerts of earthquakes. Technology, such as the Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) system is in use in Japan. In Japan, there are thousands of earthquake sensors across the country that send data to the JMA. When there is shaking, EEW is immediately sent to radio and TV broadcast stations, mobile apps, desktop apps and even to different hardware devices that can do everything from sounding alarm bells to shutting down factories and railway lines. For over 10 years now, I have been working with Japan’s EEW system and we currently have systems at REC that monitor the feed. The Japan Metrological Agency (JMA) provides a feed to various service providers who then send the data out through a websocket. It is a very fast service, even halfway around the world. The feed from the JMA provides the basic information such as a time, the magnitude, the intensity level (using Japan’s “Shindo” scale), the epicenter and in the case of larger quakes, the prefectures and subprefectures that are expected to receive higher intensity shaking. On radio and television, broadcasts are immediately interrupted and information is provided by either a live announcer at the station/network or through an automated voice. Unlike the USA, there are far fewer radio stations per capita in Japan and many are staffed 24x7. Unlike in the USA, there is no similar emergency alerting for other types of emergencies, except for their J-Alert system which is used to warn about incoming missiles from North Korea.

Earthquake alerting on the west coast

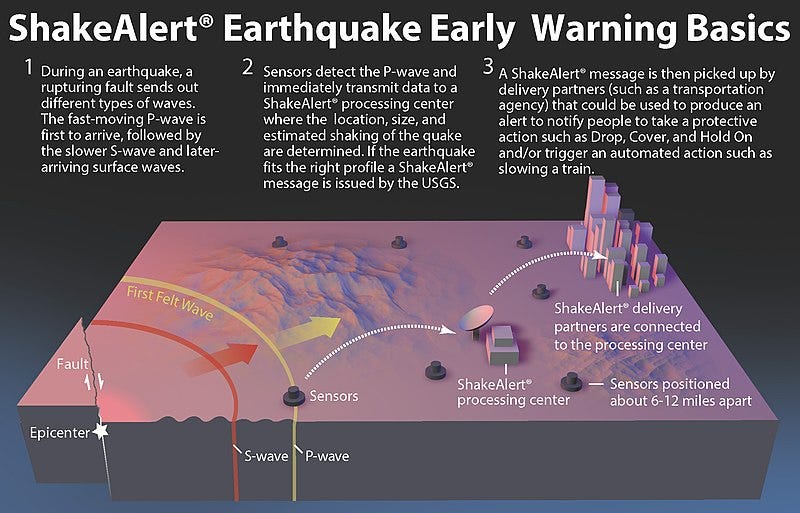

On the west coast of the United States, the U.S. Geological Survey has a system set up called ShakeAlert. ShakeAlert is the closest thing we have in the USA to Japan’s EEW system. ShakeAlert does make their feed available to developers and any applications developed must follow some very strict standards around latency. The idea is to get the message out as quickly as possible. The openness of the network allows for many of the non-broadcast applications that Japan’s EEW offers such as shutting down factories and stopping trains. Could broadcast stations ever take advantage of this? Perhaps someday. But it would require the equipment and procedures to be developed and yes, funding.

Well, we have determined that EAS in its current form was 100% useless and now, with the CAP Polling mandate, is 200% useless for earthquake information. But what about tsunami?

Alerting for tsunami

Unlike earthquakes, the threat of tsunami is easier to predict. When an earthquake happens in Japan, the JMA has specific steps they go through at certain timed moments after the quake occurs. One of those steps is to determine the threat of tsunami. When there is a tsunami warning in Japan, they use a similar data feed system to present information to broadcast stations and other electronic providers. The coastal and inland waters of Japan are divided up into about a hundred regions. A tsunami report in Japan will predict for each of these affected regions, the potential wave height and the predicted arrival time of the waves. The tsunami warning system in Japan also triggers outdoor sirens and other notification devices. In many (but not all) cases, there is a little more time from when a tsunami warning is called to when it will reach the shore. During tsunami warnings, Japanese TV stations will overlay a map of Japan on the lower right portion of the screen with the regions where alerts are active highlighted. Different colors are used based on the predicted wave height.

When a strong earthquake happens, Japan’s public broadcaster NHK stops everything on all of their TV and radio networks to provide wall-to-wall earthquake coverage. Tsunami warnings are also provided in English through a looped message that is carried on second audio program on TV and over the NHK Radio 2 network on AM radio.

Yeah.. EAS could do tsunami warnings

EAS could be effective for broadcasting tsunami alert information. While I did see on the NWS data feed that we get here at REC, that there were tsunami warnings issued by the NWS, I am not sure if those activated EAS in the Bay Area. Of course, local responder agencies can interface directly with IPAWS to send alerts through EAS and WEA to their counties. EAS units normally have text to speech capability so they can read the text of an IPAWS message that has been flagged for EAS dissemination.

As someone who has an interest in earthquakes, Japan and emergency alerting, I really hope that the industry and the government agencies take notice of what happened in California today and what Japan has been doing for nearly two decades now and that we can find a way to provide a way to provide precision EEW services to broadcasters without much financial burden on the stations, especially the small commercial, noncommercial and LPFM broadcasters.

Radio must remain the go-to place for quake/tsunami information

Radio can be relevant in times of disaster, but right now we are losing out to online resources, mainly due to bad policy coming out of DC and Sacramento. I am not sure if there’s a light at the end of this tunnel. At least for the west coast, there is some hope with ShakeAlert, if we can learn how to accept it and utilize it for broadcast use. Always remind your listeners on the air and on socials to make sure that they have an earthquake emergency kit, which includes an AM/FM radio and spare batteries. I know… Where can I find a portable AM/FM radio these days? Hmmm… You can still find them in Japan.